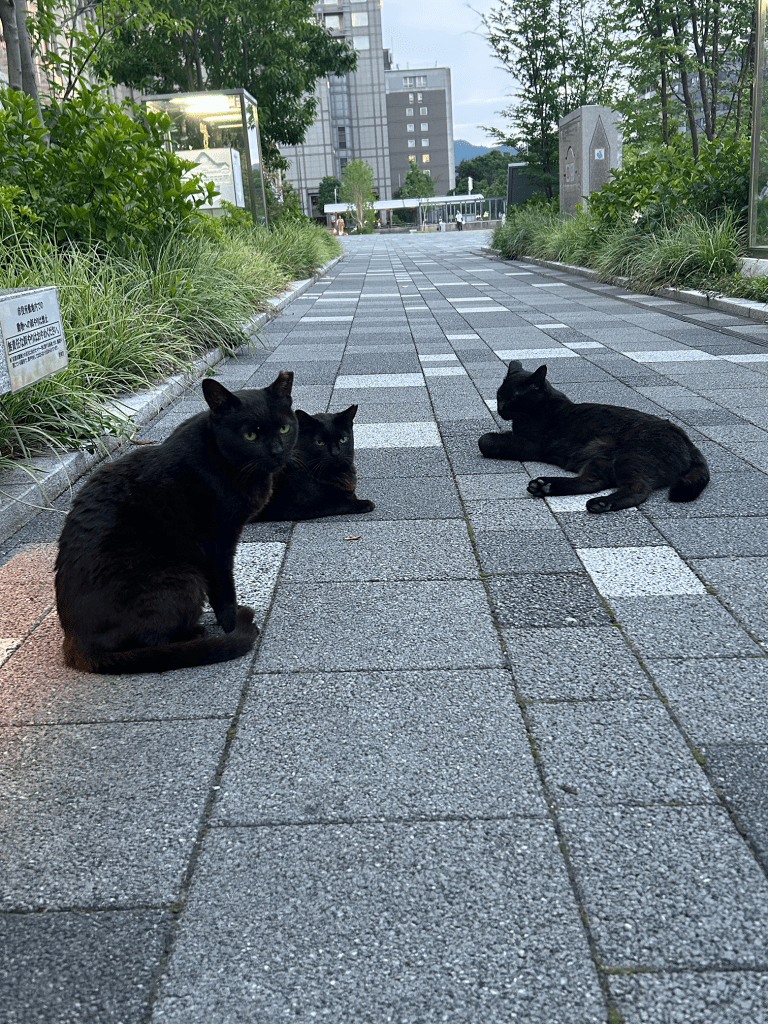

Walking down the streets of Kyoto every day going to and from my lab, there is a sense of peace that is often lacking in the stressful campus life and my busy home of New York City. The quiet streets, the mix of beautiful traditional Japanese houses and modern apartments, the huge birds and tiny critters, and the neatly kept asymmetrical gardens offer a rhythm of life that feels slower, more deliberate. In Kyoto, I lose the anxiousness that normally follows me around campus when I think about my next class, my next PSET, or (god-forbid) my next exam. The franticness that follows me around the Infinite as I push through seas of students to speedwalk to my next class as fast as possible, or the constant stimulation of New York City––car horns and crowds that never stop––doesn’t exist here. Here, I’ve been able to experience what it feels like to just be, to exist without tension, something I never imagined being able to experience with my overwhelming lifestyle.

With the slower pace, I’ve had the time and space to reflect on parts of myself that I’ve neglected. As a first-generation, low-income college student who is also the eldest-born daughter of my family, I’m in perpetual hustle mode—fighting to earn more opportunities and to prove that my parents were right for sacrificing so much, constantly afraid that slowing down means falling behind and eventually failing. My friends are typically shocked to learn that I was born in a tiny secluded village in East Fujian, China because everyone sees me as the city girl from NYC. While true, I was also the village girl who grabbed eggs from our hens and carried the basket of vegetables after a harvest. Despite being the home of my fondest memories, very few people know about my origins because of how little time I spent there.

During my first three years in the US, my parents moved from state to state in search of work, often leaving me in the care of family friends. At the time, I often found myself blaming them for often being absent from my life. I didn’t understand why my parents chose the harder life; why would they leave behind their lives to come to America with nothing but hopes for something better? My mom insisted on working while being very pregnant (twice… hello Jason, hello Patricia), and my dad pushed through every sickness and injury without breaks. Seeing them tolerate so much, I felt like I had to match their efforts to prove that their sacrifices were worth it. As a result, the fear that I would not be able to live up to the potential they have created for me followed me like a shadow from a young age.

Thankfully, I think I’ve done well, especially since my mom loooves to say that I’ve surpassed all expectations they ever had for me. My initial thought was “Wow, you didn’t believe I would make it this far???” But truthfully, their bar for me was never high to begin with; not because they think I’ll fail, but because they never wanted me to push myself this hard to reach for the stars—they just wanted me to live a happy and carefree life. Now, I’m technically living the carefree life they always envisioned, but moments of joy often came with a side of guilt.

So far, I’ve spent this summer frolicking around the streets of Japan, taking beautiful photos of sunsets, texting my friends and family about interesting encounters (like when I watched Americans walk into the store named “American Holic”). Every now and then as I enjoy this rare leisure abroad, a pang of shame will hit me:

- Why do I get to enjoy this amazing opportunity to do research in Japan while my parents can’t leave our restaurant?

- Why is it that their sacrifices assisted my success, but their lives remain difficult?

I feel grateful yet ashamed, empowered yet disqualified. I’m the one who pushed through late-night studying without support from my parents because they dropped out of middle school to start working. I’m the one that studied alone in my room to prepare for the SATs, the one getting up every day to go to lecture, the one trying to keep up at this impressive institution. However, it was not me who had to give up everything to start over across the world. It’s not me who is standing in front of the cash register from 11am-12am—it’s my mom. It’s not me with oil burns and knife scars, spending all day cooking for others but barely having time to eat food—it’s my dad. These thoughts pull at my conscience, making me wonder if I am allowed to enjoy myself like this.

The often-unspoken emotional contradictions of being a FLI student both motivate yet haunt me.

Despite knowing all the struggles my parents are going through, I found myself swept away by the novelty of this summer; the excitement of exploring, trying new foods, and doing cool research soon drowned out my worries. But, just as abruptly as I felt the weight lift off my shoulders, it slams right back down on me. One moment I’m laughing with my mom over FaceTime while getting ready to have a night out. The next, I’m wondering if she ever got to laugh like this when she was my age. When I visited Tokyo for the first time, I called my mom at midnight. I told her I had just gotten off the bullet train and that I was about to go clubbing in Shinjuku. She told me I looked beautiful, but that she was also envious of my fun adventures; her words left me with both love and pain. She told me to have fun and to stay safe, we said “I love you” (one of the few English phrases my family says to each other), and I hung up with a heavy chest. My walk to the club was filled with thoughts of how my mom’s life could look so different if she had the freedom to experience this when she was twenty. Those thoughts were incredibly loud, and it took a drink or two before I was able to get out of my own head and enjoy myself on the dance floor.

The often-unspoken emotional contradictions of being a FLI student both motivate yet haunt me. I feel confident in my intelligence, my knowledge, and my character while also often feeling alienated from both my family who never got to experience these things and from my friends, many of whom didn’t experience a similar childhood at all. When talking about our parents, I realize that I am one of the few in my friend groups with undereducated parents. There’s a level of disconnect amongst my friends who don’t understand why I push myself so hard when my parents don’t care, or why I complain about my parents’ stubbornness in refusing to take breaks but I get offended when someone else critiques them.

I can’t speak on behalf of all FLI individuals, but I think for a large majority of us, rest is something that feels almost forbidden. Whether it be pressure from our parents or internalized pressure from our own desires, it is oddly difficult for us to fully enjoy ourselves in any given moment. I’ve caught myself feeling reluctant to order takeout even when I have no time to cook, or for spending a morning doing nothing but watching YouTube, sipping tea, and listening to my “hot girl agenda” playlist. The quiet voice in the back of my head pops out to remind me, shouldn’t I be doing more? It’s not just about my achievements—it’s about being the physical representation of the hopes of a young couple in their 20s that gave up everything so I could be here. As I’m now also in my 20s, I can’t possibly imagine moving to a new country with nothing but hopes and prayers for something better, if it even existed—there was no guarantee that moving to America would be easier. For me, joy and relaxation always came with strings attached: a checklist, a sacrifice, an exchange. So even when I find myself in Kyoto having the time of my life, it takes serious effort to feel like I deserve to be here.

Their resilience became my guideline for success. If they weren’t allowed to pause in sickness, how can I justify taking a break just because I have a headache and a cough? They didn’t have the luxury of slowing down, so why should I?

It’s funny how I understand, logically, that I deserve rest just as much as the next person does; at the same time, my brain seems to do literally anything to prevent me from resting. I remember sitting in the onsen alone during our Kesennuma retreat. It was approaching midnight and I felt my body relax under the hot water, but my mind was wide awake. A detailed to-do list with deadlines flashed through my brain: that sheet for my team, that email for my club, (trigger warning) the MCAT, clinical hours and shadowing. Even when the world is completely silent and still, my brain keeps buzzing—like a fly that won’t go away even when you swat at it. It’s not that I consciously evade rest, but that even in my most exhausted state, I feel compelled to keep going. Asking for help or taking a day off feels illegal. I had a seriously horrendous cough in June and I unironically looked up “Is it bad to take 4 days off work if you are very sick” just to convince myself I wasn’t being lazy. I felt so bad about emailing my lab for the fourth day in a row that I wasn’t able to come in, like I was disappointing them.

I think part of me believes that rest is something you deserve only after you’ve achieved it all—not while you’re still trying. I know that’s not sustainable and will absolutely lead to insane burn out (because it has, multiple times!). But when you grow up watching your parents work 14-hour shifts, six or seven days a week, always complaining but never giving up, it’s hard not to internalize that same sense of duty. Their resilience became my guideline for success. If they weren’t allowed to pause in sickness, how can I justify taking a break just because I have a headache and a cough? They didn’t have the luxury of slowing down, so why should I? In many ways, I feel like I inherited that restlessness; I exist in the space between gratitude and guilt—grateful that I’ve made it this far, but guilty that I get to experience things they never could.

The fear that drives me isn’t just of failure—it’s fear of wasting the sacrifices my parents made. If I slow down even just a little, I’ll fall behind. Even though my parents have always been nothing but encouraging, that fear has built a home inside of my ambitions. I find that sometimes, I can’t tell the difference between the two. Fortunately, this escape to Kyoto has helped me begin to distinguish them.

Surrounded by stillness and beauty, I feel myself letting go of some of the weight that I’ve been carrying my whole life. I try to give myself a little kindness every day, whether it be a delicious strawberry nutella crepe or a solo dinner date at a yakiniku restaurant. Without the constant presence of academic pressure or responsibility, I’ve been able to admire the beauty of life and enjoy the company of my friends. I’d like to think that I have become my parents’ eyes, seeing beautiful rivers and sunsets in places they may never visit. I’ve become their hands, typing, pipetting, reaching for futures they couldn’t pursue. Most importantly, I’ve become their emotions too, feeling joy and relaxation in ways they rarely let themselves feel. I try to bring back a new lesson about self-care every time I go home; with each new experience of calmness, I share it with my parents hoping that it’ll give them the courage to slow down and let themselves breathe. Just like how I hear their voice and see their faces encouraging me when I’m on the verge of giving up, I want to be the voice and smiley face in their minds that reminds them it’s okay to unwind a little. It’s small things like offering to go on my brother’s field trip, or convincing them to take a nap while I make dinner. Recently, I’m nagging my mom to vacation with me in some tropical place this winter. I want to give her the vacation experience that she’s always wanted but could never afford. Good thing I’ve been saving up, so it’s looking plausible (crazy to me that it took me two years of asking before she says maybe).

My relationship with my parents started out rough because I felt neglected due to their determination to find work. As I grow older, I realize that it was just love in motion—their way of building a future for me, even if it meant being apartand all they ever wanted for me was exactly what I won’t allow myself: an easy life. No amount of brutal study sessions or sleepless nights will reimburse the years my parents gave up to get me here. But repayments and achievements were never the point, peace was. Choosing an impressive career has always felt like my way of honoring their sacrifice—through stability and purpose—but I’m starting to realize that honoring them might also mean learning how to slow down. I want to show them that our lives don’t have to be shaped only by struggles and sacrifices.

I don’t think I’ll ever fully silence the voice that tells me to keep going, nor do I want to. My dreams will always be big, whether from my own ambitions (surgeon Bridget, hopefully!!) or the silent FLI pressure. I’ll probably never escape overworking or overachieving, woven entirely into my story and my background, but I hope to bring back lessons from Kyoto for myself. Maybe I can start seeing rest not as a betrayal of their sacrifices, but as one way to honor them—by allowing myself the tranquility they never had the privilege to enjoy. If I can learn how to hold space for myself amid the chaos, then maybe I won’t just chase after fulfillment through accomplishments. Maybe I can teach that back to my parents; my compensation for their perseverance will be helping them find their peace. Someday, I hope to take them somewhere to finally relax and do the things they’ve always wanted to do but never had time for. I want to tell them “We’ve made it, it’s okay to slow down now.” Until then, I’ll keep reminding them to take care of themselves, to take breaks, and I’ll keep repeating “I love you” until they start loving themselves too.

Bridget Li is a member of the class of 2027 studying biology and is a pre-medical student. This summer, she is interning at the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) at Kyoto University, Japan.