“Nǐ shì cóng nǎlǐ?”

I lean in close over the pulsing music of the crowded beachfront Quebra Canela restaurant. My ears strain to make out what I assume to be Kriolu (Cape Verdean Creole) words I don’t yet know or a Caboverdean name I’m unfamiliar with. It takes me a second to realize that the woman is speaking to me not in Kriolu, but in Chinese, asking: where are you from?

“My tone is not that good,” she apologizes, referring to the four tones in Mandarin Chinese—inflections in pronunciation that can mold one romanized spelling into a plethora of different meanings—which often trip up non-native speakers. It’s the second time today alone—on Friday, my third day in Praia—that someone has tried to speak Chinese to me, by way of greeting.

The stranger-turned-acquaintance tells me she lived in Hainan for seven years as a university student. It’s a partnership between the governments of China and Cabo Verde, she explains, where Caboverdean students with good marks can apply to study in China. When I first decided to do MISTI here, I wasn’t aware of the ties between China and Cabo Verde. Since arriving, new facets of this relationship popped up every day—in the stories locals tell me, in the infrastructure around me, and in the conversations on politics and foreign investment.

I assumed that my East Asian racial identity would influence my daily experience here in Cabo Verde, but I perhaps (naively) didn’t realize it would be so present. One of the other MISTI interns, who is Indian, said that people here sometimes assume she is Caboverdean (apparently, she looks like people from Fogo, another island in Cabo Verde) until she starts speaking. Another intern, who speaks fluent Brazilian Portuguese, says people are usually satisfied to infer some sort of Portuguese heritage (in 1975, Cabo Verde gained its independence from Portugal, and Portuguese is the official language used in government, the news, and education).

Earlier this same day—Friday, my third day in town—one of our taxi drivers starts talking to my roommate in rapid-fire Portuguese. I manage to catch the words “Estados Unidos.” The driver looks back at me and scoffs. I hear more words, including “Koreana” (to clarify, I am not Korean). After we get out of the taxi, my roommate translates the driver’s concluding comment: that while we might have white, yellow, or brown skin, we all have red hearts.

‘Between Race and Ethnicity’

I have spent my entire life in large metropolitan areas of the US—raised in Los Angeles County before moving to the East Coast (Boston and New York City) for college. All of these regions have large and diverse Asian American populations from a range of ethnic backgrounds. Even so, the question of ‘Where are you really from?’ is one that, as for many children of immigrants, I have come to expect.

“Chinês?” Chinese? For the first few days here, when someone asks me this question, curious, confused, or perplexed, I answer ami é di Merka—I am from America. This is always how I’ve identified. But my conversation with another MISTI intern here, who is an international student, helps me to realize that this differentiation may be more particular to the US than I assumed. “In other places, it can boil down to what you look like,” she tells me.

At MIT, I’m involved in the Asian American Initiative—where our mission statement is to promote pan-Asian advocacy, allyship, and civic engagement. It is this sense of seeking collective solidarity in the “Asian American experience” which has shaped much of my identity development throughout college. I still believe in the power of this work, the forms of advocacy and creative practice which have allowed me to form a deeper consciousness of my racial identity that I lacked growing up. However, I have wondered at times if there is some part of myself I am alienating in the process. Now, when I try to speak Mandarin with the elderly store owners in Boston’s Chinatown or in Allston and receive replies in dismissive English, I wonder if there isn’t some piece of my heritage I’ve left behind.

From my first impressions as an outsider, I interpret this dynamic as a tension between embracing a diversity of cultural influences, heritages, and histories while also aiming toward a uniting sense of national identity.

Cindy Xie

My first two weeks in Cabo Verde have forced me to think carefully about the distinction between terms I sometimes conflate, such as race, ethnicity, and nationality. Cabo Verde is known as a heterogenous place of mixed backgrounds, cultures, and languages. The country is also known for its centuries-long global diaspora, with the number of Cape Verdeans living abroad estimated at 700,000, or double the number of residents in the actual country. In her 1993 book Between Race and Ethnicity, historian and sociologist Marilyn Halter describes “a shared sense of liminality, that in-between, neither here nor there…[a] borderland positioning and variegated inflections of Cape Verdean representations of identity” that she observes among members of the diaspora. From my first impressions as an outsider, I interpret this dynamic as a tension between embracing a diversity of cultural influences, heritages, and histories while also aiming toward a uniting sense of national identity.

White, yellow, or brown skin…red hearts. Perhaps this is also the taxi driver’s way, then, of saying that “you are what you look like” and asking about it bluntly, with the assumption of an underlying shared experience. But I can’t say that for certain.

Reconnecting Through Language

That same Friday, my third day in town, we join in the Cabo Verde LGBTQ+ Pride Parade. Sweating from the heat and the incline, we pass a store in the Plateau (Praia’s historic centre) called, simply, Chinatown.

“What is that?” I ask the person next to me. They shrug, replying nonchalantly, “a store.” We continue on by.

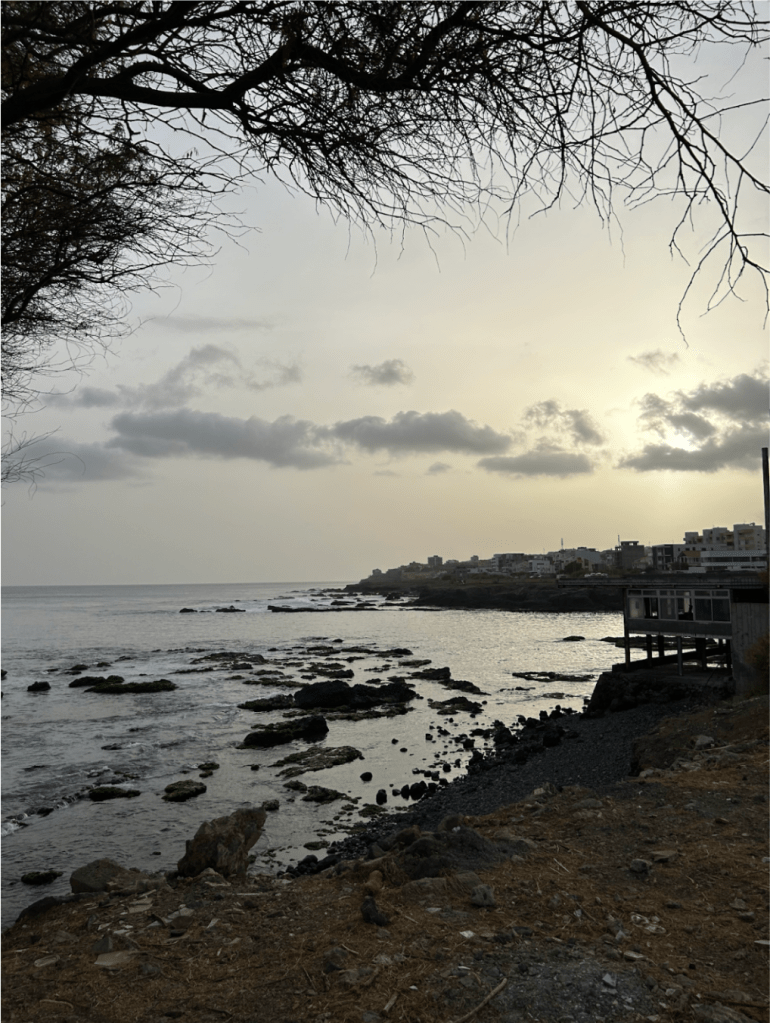

On my seventh day in Praia, I am out on a sunset stroll in my neighborhood when I pass another one of these stores—a minimarket this time—with a generically ethnicized Chinese name. This time, I go in. I don’t need anything, but I am curious to see what reception I will get—whether I will be welcomed.

No one acknowledges my presence at first. I wander around for ten minutes, feeling the gaze of the employees on my back. Finally, I grab a random bag of biscuits and approach the storeowner at the cashier, who is Chinese. Her face is stoic at first, but when she sees me, she breaks out into a smile. “Nǐ hǎo,” she says. “Nǐ shì zhōngguó rén ma?” Hello, are you Chinese?

I reply in Mandarin with a ‘yes, but’—yes, my parents are from China, but I was born in the United States. We strike up a conversation. I always considered my Mandarin—cobbled together from speaking to my parents and family friends growing up—poor, conversational at best. Yet especially compared to my Kriolu, I feel lighter now, expressive again. The storekeeper and I exchange phone numbers. I finally downloaded WeChat—the quintessential Chinese instant messaging app I have put off downloading for years; I had never truly felt that I needed it—before this moment.

Diasporas in Conversation

“Chinês?”

Now, two weeks into my stay in Cabo Verde, I simply nod, leaving out the “but” unless the asker wants further elaboration. It can still be frustrating. But in my head, a new meaning to the phrase ‘Where are you really from?‘ is also starting to form.

There’s a word here, in Kriolu: sodadi, from the Portuguese saudade. It translates roughly to “longing,” but my coworker tells me that doesn’t quite capture it. “It’s not just missing someone,” he explains. “It’s more than that.”

“Is it like nostalgia?” I ask.“Not quite…deeper,” he replies. “Sodadi can kill someone.”

Perhaps ironically (or not), it is upon leaving the United States that I’ve developed a newfound desire to reconnect with my ethnic heritage as a second-generation Chinese American—not simply a second-generation Asian American. I’ve never described myself before as part of a global Chinese ‘diaspora,’ but the more I travel, the more I become interested in seeing it this way. Here in Cabo Verde, a country defined at its core by its diaspora, I’ve begun to look back at the forces of migration in my own lived experience—and about the multifaceted ways through which their consequences can be interpreted.

To understand how race and ethnicity interact with nationality, as well as the nuances in how members of any diaspora understand their identity in terms of the particular migration histories that have spurred it, feels important in ways I don’t yet fully know how to articulate. On one hand, these stories counteract, or add deeper complexity, to the essentializing tropes that spur anti-immigrant sentiment in countries around the world. Within a nation like the US, they are also critical to revealing the nuances within the multifaceted communities contained within an umbrella term such as “Asian American and Pacific Islander.”

But on some level, I think I’m just interested in the sheer fact of these migration stories being told on their terms: honoring the forces, both positive and oppressive, which motivate individuals to uproot their lives and seek out new horizons. Giving a voice to the uniqueness of each family, city, or country’s narrative while also placing it within a collective whole. Tracing lines between history, memory, and the present. I can’t say I know how I’ll feel at the end of the summer, but I’m appreciating the act of documenting the process.

My name is Cindy, and I am a rising senior majoring in Urban Studies & Planning with minors in Biology and Anthropology. This summer, I am researching climate change and its health impacts at Universidade Jean Piaget de Cabo Verde (as part of the first MISTI cohort ever in the country).